A recent blog post from Verisign questions whether the domain aftermarket adds any value whatsoever for end users. The recent Verisign post has been widely discussed and criticized within the domain community. In this opinion piece I examine and respond to the claims and arguments in that post.

As background, Verisign have for some years managed the .com top level domain (TLD). Many lobbied for either a competitive bid, or at the very least the cap on wholesale prices of .com, that has been set at $7.85 USD for a number of years, should be maintained. In a recent agreement the price cap will stay in place for two more years, but after that, subject to ICANN agreement, increases of up to 7% per year are allowed in each of the following four years.

It should be stressed that their blog post was made after the company had secured a 6 year extension that included 4 years of price increases.

What About Unregulated Registrars?

The first argument in their post is that controlling wholesale costs does not help control end user domain costs because registrars can charge whatever they wish. Verisign is not permitted to sell directly to end users who must purchase domains through ICANN approved registrars. Note: throughout when a quote is from the Verisign blog I indicate that as signature on the quote. Quotes without that are from this document.

“However, the price caps don’t help businesses and consumers who buy from registrars, since registrars can charge retail prices for .com domain names as high as the market will bear.”

–Verisign

While it is certainly true that the price caps don’t directly control the prices registrars charge, in practice competition results in prices that closely track the wholesale price. There are literally thousands of ICANN authorized registrars and keen competition among registrars on price. Tools such as TLD-list and DomComp make it trivial to find the lowest current costs for registration, transfer and renewal of domain names in any TLD.

Registrar competition results in prices that closely track the wholesale price.

The Verisign statement that ‘price caps don’t help’ is demonstrably false. Registrar charged prices to end users (and domain investors) will go up when wholesale costs to registrars go up.

Can We Talk About Domain Speculation?

The article then goes on to discuss the secondary domain market.

“But there is also an unregulated secondary market – led by domain speculators – hiding in plain sight. There, some speculators buy domain names at regulated low prices, then sell them at a far higher price. This secondary market is as old as the domain name system itself. However, since the wholesale price cap was imposed on .com in 2012, the secondary market has expanded in ways that exploit consumers.”

–Verisign

It is true that in the secondary market domains normally sell at prices well in excess of the initial registration fee. In the resale market many .com domains sold have been registered for a decade or more and have passed through multiple hands, so the acquisition price is often not the registration price. Even the simple break even price would require accounting for holding costs.

The important point, though, is that domain investors have taken substantial risks that the domains will not sell at all, or if they do sell, at a loss. The daily domain market sales report put out by NameBio highlights domains with a previous sales record, and not infrequently the price goes down by 90% or more. An analysis I did indicated that domains that sell a second time are more likely to go down in price. There is real risk in being a domain investor. There needs to be significant compensating rewards on the domain names that do sell to make up for the larger number that do not.

Those who hold these domain names have taken substantial risk that the domains will not sell at all, or if they do sell it may be for a loss.

While it is true that the secondary market expanded in new ways since 2012, I think there is no causal relationship, as implied in the post, to the price cap period. Machine intelligence reached a level around then that allowed automated buying and selling of domain names. The consumption of margarine and the divorce rate in the state of Maine nicely correlate over decades, but that does not mean one caused the other!

I believe that the word ‘speculators’ and the phrase ‘hiding in plain site’ were deliberately used to negatively portray those involved in domain investing. To some the wording suggests an activity that is barely legal and somewhat shady. This implication is unfair and incorrect.

Let me take a look at the broader idea of speculation. Consider business startups. Those who invest at the early stages could legitimately be considered speculators. They speculate on which companies might achieve technical and business success. Most will fail, but a few will succeed.

In order to make up for the losses on the many failing companies, returns must be significant on the few that do succeed. These business speculators play the critical role of funding early stage research and development to bring innovations to market. The business world could not succeed without the ‘business speculators’.

But, you might say, domains are different, the domain ‘speculator’ is not necessary or even helpful. But there you would be wrong. Let me explain.

Domain Names Are Created

Domain names are created, in a way not dissimilar to a work of art or literature. The combinations of words, spellings, acronyms, and more come together in a creative product, the domain name. In the brandable niche, the word itself is often totally made up.

Domains are not just any combination of letters or words, but a sequence that meets certain aesthetic and marketing needs. Many of the same principles such as simplicity, elegance, functionality and impact that apply to product design are equally relevant to the design of a strong domain name. Ideally, even a made-up word hints at the nature of the business while not boxing in the future directions. Whether made-up or not, the domain name optimally evokes positive emotions in a memorable way.

Domain names are created, in a way not dissimilar to a work of art or literature.

If you don’t believe me, look through a list of domains that have recently sold. Yes you will find some sequences of numbers or single generic words, and some two or three word domains that are obvious, but you will also find fantastically creative works of domain art.

In this way investing in domain names is more like investing in works of art than startup businesses. The domain investor may be a word artist directly, or they may be buying and selling creations by others in the domain aftermarket.

Investing in domain names is more like investing in works of art than startup businesses.

Just as those who invest in local artists help promote and encourage art, those in the domain market are directly responsible for creating, promoting and bringing to end users domain names that make a difference.

Does The Domain Aftermarket Really Add Nothing?

This brings us to the most criticized part of the Verisign blog post.

“Flipping domain names or warehousing them to create scarcity adds nothing to the industry and merely allows those engaged in this questionable practice to enrich themselves at the expense of consumers and businesses.”

–Verisign

While this might be interpreted more narrowly, many took it as applying to everyone in the domain aftermarket. Do they really mean that someone who made a clever brandable name, or put together two words in a creative way, or finds a playful spelling, or that perfect memorable word, or a thousand other domain works of art has contributed nothing?

The domain investor who brought a domain opportunity to a big company that rebranded on that, they contributed nothing at all? The domain broker who had the connections to bring a business leader in touch with the person holding just the right domain name – no value in that at all? Everyone in the domain aftermarket, they add nothing? Seriously, Verisign?

Do they really mean that someone who made a clever brandable name, or put together two words in a creative way, or finds a playful spelling, or that perfect memorable word, or a thousand other domain works of art has contributed nothing?

Verisign seems to think that domain investing is like happening to be able to buy the greatest concert tickets, then easily sell them the next day for 20 times what you paid. Are they really that isolated from what happens in the world of domain names?

Let’s Talk Domain Prices

The Verisign piece would leave you with the clear impression that domain investing is highly lucrative for almost everyone. They extract four example prices from the four million at HugeDomains and imply those prices are somehow typical of prices asked and received. It is certainly true that a few individuals who invested heavily in domains at the start of the Internet age, seeing an opportunity before others realized it, have high net worth. The implication is left that domain investing is highly profitable for most.

Let’s start with their four domain price examples. It is literally like going through eBay, finding some ridiculously priced items, and saying ‘See everyone is making a fortune on eBay.’ The fallacy in the argument is the assumption that the products sell at those prices and that most domains are similarly priced.

Let’s look at some numbers: real numbers. We are fortunate that many of the main venues for selling domain names in the aftermarket report sales to the NameBio public database. Anyone can search this database so there is no reason to not use objective data. It should be noted that the entire Verisign post does not mention NameBio or any other specific source of quantitative information.

During the past 12 months the average sale price (at least for NameBio recorded sales) for a .com domain name was $1191, based on the 69,586 domain sales in the database. You might react by saying, not as much as I thought but that’s still a huge price compared to registration cost. There are three important factors not to overlook, however.

During the past 12 months the average sale price for a .com domain name was $1191.

The average price is highly influenced by a few large sales that the vast majority involved in the domain aftermarket will never benefit from. For example the name ICE.com sold to a stock exchange for $3.5 million. If you take out just the 11 largest sales, from the 69,586 sales, the average price drops by almost 15% to $1049. About 2/3 of the domain sales for the year (44,161) were for $400 or less. Only about 1.2% sell for $10,000 or more. Yes sometimes domain names do sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, or millions even, but not very often.

About 2/3 of the domain sales for the year (44,161) were for $400 or less.

But really it is somewhat more negative price wise, as NameBio do not publicly report the sales less than $100 so a much larger fraction really sold for very low prices, and the average price, at least for the sales reported to NameBio, is even lower.

The most important factor however is that the vast majority of domain names never sell. Ever. The price charged for those that do sell has to be large enough to make up for the many that do not sell (or sell at a loss). It is just like handling art from new artists – you will make a big profit on a sale now and then, but most of the time the works will either sell for very low prices or not at all.

The vast majority of domain names never sell. Ever. The price charged for those that do sell has to be large enough to make up.

NameBio receives reports from certain secondary domain sales venues and not others. Some suggest there is a bias since perhaps more sales are wholesale (one domainer to another) versus retail (domain investor selling to an end user). That may well have some validity, it is tough to be sure. What is clear is that the vast majority of domain names do not sell, and most that do sell, do so for $1000 and less.

While $1000 is not a trivial amount, for a reasonably sized business it is small compared to many costs. Almost certainly what they pay for consulting, marketing, branding and similar services are well in excess of the cost of the domain name, at least averaged over a few years. The Verisign post is remarkably absent any evidence that end users consider that they are paying too much in the domain aftermarket. It would seem to me that this should be a central part of their argument.

The Verisign post is remarkably absent any evidence that end users consider that they are paying too much in the domain aftermarket.

Clearly it would be wrong if domain investors were sitting on a domain only suited for a single business, and refusing to sell it at a reasonable price. However, very strong cybersquatting laws, the trademark system, and the efficient UDRP process means this practice is not allowed.

Is Domain Investing Even Profitable?

I posed less than a month ago the simple question “Is domain investing profitable?’ I mean obviously some individuals and companies are profitable, and some are losing money, but overall what is the situation? That analysis is relevant to a consideration of the accuracy of the Verisign post’s portrayal of a lucrative aftermarket.

My rationale to be interested in profitability was meeting online many people getting started in the domain community who had not made anything at all yet. In many cases these were students, those who had lost their job, retirees, and others who could not personally afford to lose much. I wanted them to have a realistic picture of the expectations for profit in domains. Too many ‘flip for quick profit’ books and articles inaccurately portray this as an easy way to make a living. So what did I find?

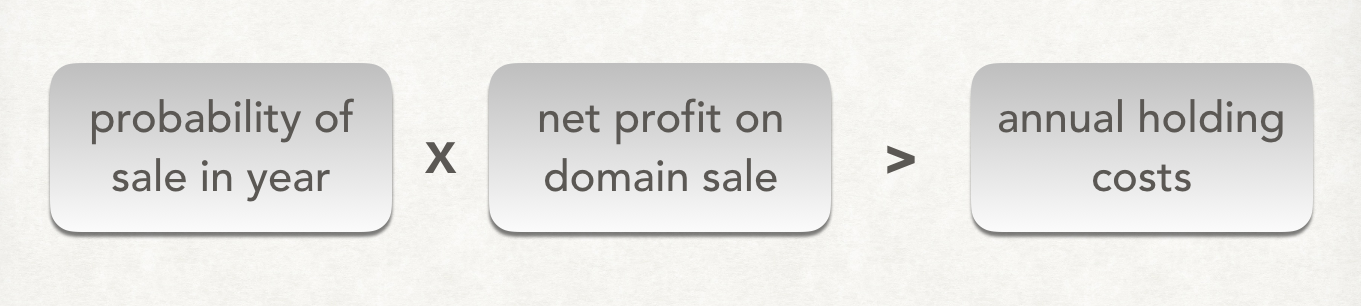

The idea of what is profitable is easy to formulate in the following equation.

If, for example, there is 1 chance in 100 that a domain name will sell in a given year, and if it is anticipated that it will sell at $900 net profit, the domain name is probabilistically worthwhile if, and only if, the annual holding costs (domain registration and other annual costs) are less than $9. Note that realistic numbers like these show how close the industry is to break even.

It should be noted that if there is revenue coming in, through monetized domain parking for example, that can be used to defray the annual costs. However, changes in how information is served on the Internet has made parking revenue in recent years almost nonexistent for most.

You can see my analysis, complete with explanations of assumptions here. I ran 7 different models, and 5 of them show domain investors, on average, lose money. It is true that the most likely numbers (the first model) did result in about 30% profit, but that was assuming nothing for the cost of money invested. It also assumed that domains sell at the average price, whereas for most the median would be a much lower and more appropriate measure. With median price the analysis shows that over the entire industry the domain aftermarket results in a loss for investors. Really.

For most domain investors this is a risky, at best marginally profitable enterprise.

For most domain investors this is a risky, at best marginally profitable enterprise. It is not at all like having a guaranteed 6 year contract extension to manage the most desired TLD without competition.

The domain complex should work toward the goals of keeping costs to end users reasonable, while at the same time leading to profitable returns on investment that take into account the high associated risks.

How Do Wholesale Prices Impact Aftermarket Domain Prices?

As the profitability equation demonstrates, if we are to operate at break even levels, each $1.00 increase in wholesale registration cost (assuming the registrars add no markup) will require about a $100 increase in the average aftermarket domain name price. This assumes a 1/100 ratio for the fraction of .com domain names that sell in any one year, a ratio widely used in the industry.

The Verisign blog post argues that the price cap has no influence on domain resale prices. I would argue that the evidence suggests that each $1 increase in wholesale .com price will lead to about $100 increase in domain aftermarket sales prices. By the end of the four 7% increases, if they come to pass, after compounding just over $300 will have been added on average to each domain resold in the aftermarket (assuming that everyone involved is willing to simply break even).

….each $1 increase in wholesale .com price will lead to about $100 increase in domain prices.

The reader would be right to say: how inefficient! Any given domain name has just 1 chance in 100 to sell in any given year! I think there are ways to improve that through more efficient aftermarkets, better education on domain names for business leaders, new uses for domain names, more contact between branding firms and domain investors, and a more highly informed domain aftermarket community so that fewer poor acquisition decisions are made. The Verisign post could have more usefully proposed solutions rather than say the whole domain aftermarket adds no value.

How Large Is The Resale Market Really?

The Verisign post estimates the total amount of ‘scalping fees’ (a term I object to, by the way). They write the following.

“So how large is this market? The answer may shock you. Verisign estimates that over $1 billion in annual secondary-market sales of .com domain names can be documented through publicly available data.”

–Verisign

Well their estimate shocked me because I know that for the past year, according to the publicly available NameBio database, those 69,586 domain sales totalled $83.1 million. So how do they get $1 billion or the $1.5 billion they actually use a few lines later? I have no idea and they provide no source link. Apparently someone in Verisign gave them one figure and a couple of people in the domain industry gave the other. They don’t specify who.

According to the publicly available NameBio database, those 69,586 domain sales totalled $83.1 million. So how do they get $1 billion or the $1.5 billion they actually use?

As mentioned earlier, everyone realizes many sales are not in the NameBio database – e.g. most sales on Afterniic and Undeveloped are not reported. But is it really a factor of 18? I don’t think so. In my model I used a correction factor of 5, close to what many in the industry suggest (i.e. I assumed that only 20% of the actual sales are recorded in NameBio).

But there is another factor to consider: a significant part of the $83.1 million was not to end users, but it was purchases of domains by investors hoping to resell the names. Many drop-catch, GoDaddy or Flippa auction sales reported on NameBio are sales to domainers. So they are counting what is a cost to domainers, and treating it like revenue! When this is taken into account the actual sales volume in a year would be substantially less, and you would need a much higher ratio than their hypothetical factor of 18 to get to their figures, probably high 20s at least.

Why Isn’t Everything Regulated?

The Verisign post frequently refers to unregulated registrars, unregulated domain investors, unregulated marketplaces, etc. as though they were comparable to the .com registry. Although it is true that these are unregulated (at least in the sense of not having price caps), there are thousands of registrars competing against each other mainly on price. There is price control through competition.

While people and companies can, and do sometimes, ask ridiculous prices for a domain name, that is tempered by the fact that there are nearly a million domain investors with at least 30 million domains for sale at any one time. Yes, I could ask $500,000 for a domain but no one needs buy it at that price and they have alternatives. The aftermarket price structure, like that in actual real estate, is controlled by competition.

There are at least 30 million domain names for sale at any one time. They provide price control through competition in an efficient domain aftermarket.

It is true that the secondary marketplaces like Sedo, Afternic, Flippa, Undeveloped, and GoDaddy do not have their commissions regulated. But they are in competition with each other. As a result, commissions are generally not very different from the 10 to 15% figure. As well as competing with each other, domain investors can use their own hosting landers, or services like Efty, so they can, if they want, efficiently connect to potential customers without marketplace commissions at all.

The difference is that Verisign, as caretakers of the .com TLD, have an absolute monopoly on the world’s most desired and valued TLD.

The difference is that Verisign, as caretakers of the .com TLD, have an absolute monopoly on the world’s most desired and valued TLD. Registrars can’t buy .com domain names at wholesale from someone else. That is why a competitive bid process, or lacking that oversight on wholesale domain prices, makes sense.

What If There Was No Domain Aftermarket?

But what if we could do away completely with the domain aftermarket? No more domain investors, no more brokers, no aftermarket venues. Just individuals who could supposedly still register any domain they wanted. Some would register domains and simply collect them. Others would try to sell them as individuals but without the infrastructure we have in the domain aftermarket. The key question is would end users be better served?

Occasionally end users would get a domain at lower cost, either because no one had registered it or the person who had was willing to sell it cheaply. However, in many more cases without domain investors listing domains on marketplaces, it would be inefficient or simply impossible to obtain a desired domain names. With privacy it would be challenging to even make contact. The current system is relatively efficient (it could be more so) in matching those seeking domain names with those holding names. Also the NameBio database of about $1.6 billion in sales data covering several decades provides evidence about reasonable prices to both buyers and sellers. Some also turn to automated or human appraisal information.

It is ultimately better that many domain names are held by investors who want to sell them, rather than by non-dealing domain collectors who might forever keep a valuable digital asset out of circulation or inefficiently try to sell it at highly variable pricing.

It is ultimately better that many domain names are held by investors who want to sell them, rather than by non-dealing domain collectors who might forever keep a valuable digital asset out of circulation.

Why Is A Passionate Domain Community Important?

NamePros has over a million registered members. There have been more than a million discussion threads, with more than six million posts in total. It is an incredibly active place. Domain investors debate trends in names, aesthetics, sales analyses, appraisals, marketplaces, registrars, sales techniques, sales techniques, legal aspects, and so much more.

While heated discussion sometimes leads to comments that would better have been left unsaid, it also can be a kind place. There is genuine shared joy at success, and encouragement when things look dismal. Members help each other daily in hundreds of different ways, some on public threads and some on individual messages.

Why does this matter? I think the health of the domain world, more than any other single factor, depends on an engaged community of domain proponents. Domain names will be more effectively used when domain names have advocates who appreciate their worth. The Verisign post, perhaps not deliberately, has dealt a blow to this community.

The health of the domain world, more than any other single factor, depends on an engaged community of domain proponents.

I do not know ICA well, but I did look through their list of members, especially the individual members. The main advocates and innovators in the domain community are there. The people who have delivered names for game-changing rebranding are represented amongst their membership. Their members are respected leaders and innovators who have, in some cases, put decades into building the domain community. I seriously regret that Verisign made the decision to attack this organization, and to do so is misguided in my opinion.

Final Thoughts And A Call

While initially the Verisign post angered me, now, upon reflection, I am more sad than angry. I am sad that an opportunity for the domain community to work together to control prices and efficiency has been, perhaps irretrievably, lost.

The essential point that a domain aftermarket with smaller margins coupled with higher probabilities for sale could be of benefit to both investors and domain users is both true and important. Verisign were correct to point out that we should be alert to all of the contributors to domain costs, and not simply the wholesale registration cost. Ridiculous prices and holding resolutely and unreasonably to those prices benefits no one.

By not meaningfully developing those points, and instead to attack in essence the entire domain aftermarket, the post morphed from useful to destructive.

I would like to humbly suggest that Verisign should take down the post and apologize to the domain community as well as to ICA directly. I am not sure what the motivation for the post was, and perhaps that does not really matter anymore. To me the most divisive part of the post, the statement that the domain aftermarket adds no value, is simply untrue. Verisign must clearly say they were wrong in saying it.

Verisign did not create .com, or establish it as the world’s standard, but the company has done a good job of retaining the esteem of the extension. Verisign is the caretaker for the next 6 years (at least) of the most respected, valued and used TLD. Their success will depend in no small part on an educated, innovative and engaged domain aftermarket. The success of that aftermarket in turn depends critically on .com being efficiently managed.

Their success will depend in no small part on an educated, innovative and engaged domain aftermarket.

It is sad that a company entrusted with the most important part of the domain universe seems to so incompletely understand domain investing and the passionate, creative, innovative and skilled community that are active in the domain aftermarket.

It is sad that a company entrusted with the most important TLD seems to so incompletely understand domain investing and the passionate, creative, innovative and skilled community that are active in the domain aftermarket.

I hope that it is not too late to turn back the clock, and to replace their post with a more accurate, constructive and respectful one.

The opinions expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the view of NameTalent its supporters or advertisers. Disclosure: The author of this opinion piece does not own Verisign stock, owns only a handful of .com extension domains, is not a member of ICA, and did not sign the petition organized by ICA. He does participate in the domain aftermarket as both a buyer and seller.

Thanks, Bob for your insightful take on the recent Verisign blog post, we couldn’t agree more with all of your points. This is a must read for anyone from the domain community!

Thank you for your kind comments. Especially coming from Sedo, that really means a lot to me! Thanks for being a NameTalent reader! We look forward to your views on future posts.

Bob

Well written, researched and opined. Everything the Verisign blog post should have been.

Hello Bob , once again great researched article and worth reading for domainers community…